December 14, 2015 • Musings

The below post was written by Elaine for the Clark Hulings Fund’s blog and it was originally published in December 2015. Elaine is a quarterly contributor to the Fund’s online publication.

Working in the arts comes with some pretty fantastic perks, not least of which is being surrounded by incredible professionals doing incredible things. There is a shared sense of civility among those of us in creative spaces that I completely adore. There is value beyond our physical exertions. We emphasize our citizenry in addition to our creativity.

We are a community.

“Community” is derived, not surprisingly, from Old French comunité and Latin communitatem, both meaning “everybody” or “society, friendly intercourse, affability.” There is a spirit of togetherness that runs through the word, both in its history and in its use.

I find the notion of community particularly compelling now, in light of world events and the shared response and support to those events. The world, at its best, is a community in action.

In reading this quarter’s edition of Kinfolk magazine (Issue 18) I counted 73 uses of the word “community.” Perhaps I was primed to watch for it; perhaps this issue, which focused on creativity and design (two fields where community reigns supreme), would naturally contain liberal use of the word; perhaps simply the holiday season encourages us to yearn for community around us. There were 157 pages in total within the issue. Seventy-three uses of a word on 157 pages—nearly half of which only contained images—is absolutely delightful.

As I was counting words, I noticed related words appearing more than once.

Comfort is a “feeling of relief,” also derived from Old French. Our communities can be a source of comfort.

Commit is to “unite, connect, or combine,” derived from Latin. Our communities unite us. Our challenges unite us. Our successes unite us.

Are you sensing a theme? “Com” is the part that unites us, that brings us together.

I was delighted to notice this uniting theme in words extend to business settings as well. Because business themes, knowledge, and expertise is useful when shared with a community. In isolation, it is considerably less useful. It is lonely.

Commission is “authority entrusted to someone,” derived from Latin. The commissioning of a work or a task can build community, especially among unrelated parties, say for example a commissioner and an artist. They may share a common language, but they have uncommon ways of expressing that language.

Commodity started as a benefit (Middle French), then it evolved to be a convenient or useful product.

A company (Old French) is a “large group of people, a society, or a friendship.” The origin differs from the disparaging way in which we sometimes refer to companies, especially those from whom our values differ. The foundation is with people. And people have—at least—our shared species in common.

Competition (Latin) began as a “contest for something, a rivalry.” Only later did it become a noun to describe those against whom we compete in business (1961).

Complex (French) means “of many parts.” Building communities can be complex; mastering business tasks can be complex. But that simply means there is a lot going on. There are many parts. Those individual parts aren’t necessarily any more challenging than a complex piece of art, which is also comprised of many parts.

Our communities can help us break down the complexity of the unfamiliar. And build familiarity and common knowledge in the process.

The word “community” and its related words are indeed common (Old French, belonging to all). And that is fitting isn’t it? The common nature of these themes reflects both our craving for community and our need to describe it… and its absence.

We communicate information by way of expressing our thoughts and ideas with each other. We don’t even need words to communicate. Our art can do that too.

Art and business transcend language, especially when either is done really well, to make a common point, understood by all. Both impart information. Both originate with people. They have a common root.

We can embrace this common root as we incorporate business practices into our studios. By recognizing the shared foundation of business and art—people coming together—the two seem less divergent.

Of course we can consider creative ways to plan financially, including budgeting to ensure our creative, personal, and professional goals are met.

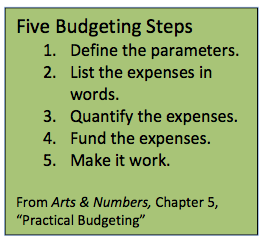

In fact, the best budgeting processes begin with goals. As I’ve described in other settings (like the Artistic Budgeting podcast from College Art Association and in Arts & Numbers), the foundation of a successful budget is a goal. The first step of the budget process is to identify the parameters of the budget. What are you budgeting? What is the time frame? What is the budget’s goal? As long as it connects to something that matters to you—within your studio practice or in your life more broadly—the budget shares a common foundation with your creativity.

In fact, the best budgeting processes begin with goals. As I’ve described in other settings (like the Artistic Budgeting podcast from College Art Association and in Arts & Numbers), the foundation of a successful budget is a goal. The first step of the budget process is to identify the parameters of the budget. What are you budgeting? What is the time frame? What is the budget’s goal? As long as it connects to something that matters to you—within your studio practice or in your life more broadly—the budget shares a common foundation with your creativity.

It exists in support of your creativity, rather than in opposition to it.

And as anyone with any experience in community cultivation knows, common ground—any common ground—can be the foundation on which to collaborate in support of some shared goal, big or small.

Our families are communities because we share a history, and sometimes DNA. Our friends form our community based on shared interests and experiences. Our colleagues make up a community because of shared appreciation, shared knowledge, and sometimes shared values.

By acknowledging the value of community, both in business and in creativity, we can take very real, concrete steps to prioritize this value within our budgets.

The second and third steps in the budget process are to list the expenses (all of the expenses you can think of related to the parameters you identified in step 1) and quantify them (usually with a long break between steps two and three).

Listing the obvious expenses is easy: Studio rent, utilities, supplies, insurance, marketing, web hosting, etc. Once we starting thinking about community, though, we identify additional expenses that might be less obvious.

Do we pay to participate in certain organizations, professional communities, at a national or local level? Do we pay to attend certain events in support of our community? Do we share meals or coffees with members of our community, fostering that community and cementing its impact over a latte? Do we contribute to others in the community by purchasing work? Do we collaborate on shared promotional endeavors? Do we attend classes to build our knowledge and our communities of learners?

These potential expenses connect to the idea of community, and they come with a financial cost (usually) as well. By including these line items in our budget, we are best aligning our communal values with our financial expenditures.

Our communities can help budget as well. It is from our communities of support that we learn tremendous amounts of knowledge. Is membership in that particular organization worthwhile? Do you derive value from this particular marketing strategy? Did you have success at this festival last year? Would you want to split the cost of a booth?

This shared knowledge and common language makes the budgeting process easier. We don’t have to rely solely on our own knowledge and experience to make value judgments about our expenditures. We can draw upon the common expertise of our community to inform our choices.

We can even draw upon the common expertise of our community to improve our budgets. A set of fresh eyes on a budget—particularly during Step 5 “Make it work”—can be a source of creativity. What have we forgotten to include? What optimistic assumptions have we made? How do our budgets align with others’ budgets within our communities?

Building a community budget group—a small group of four or five artists to help keep each other on track when it comes to building, editing, and sticking to a budget—is a delightful use of a community.

And there’s an added benefit (beyond a functioning budget) as well.

Supporting our creative community is good for our own business. Supporting each other is good for our own studios. Not only can such support inspire creativity; there is a very real, personal connection that comes from engaging with our community, even if we engage with them around an arduous task, like budgeting.

The community fills us up with good feelings.

And in fact, the word complement (Old French) means to fill up. It shares a common root as well. That is indeed what community does for us. It fills us up, fuels our creativity and supports those around us (both literally and figuratively).

So as we embrace the end of this common year, one that has been full of worldwide ups and downs, let us embrace our shared community and use it to our own, shared financial advantage.

For it is within this community that complex conversations become simpler, even if the solutions remain elusive; competitors become supporters, even if the common ground is hard to see; and divergent ideas find common ground. Even common financial ground.

For Further Reading

Artistic Budgeting podcast from College Art Association (January 2013)

Kinfolk is a slow lifestyle magazine published quarterly by Ouur (Issue 18)

Put This Into Practice

Budgeting Basics | $49

Part of the STARTING SMART online learning series from Minerva Financial Arts