July 27, 2015 • Arts Orgs

This post by Elaine Grogan Luttrull originally appeared as a guest post for the Evans Consulting Group.

Can entrepreneurship be taught? Or is it an inherent set of traits found in some, but not others?

I’d argue there is a bit of both. Certainly some skills are necessarily inherent: a positive disposition, determination, and comfort with flexibility. Others can be cultivated: Grit, creativity, and leadership.

And there is something delightful about honing those skills in unpredictable places. There is no shortage of articles highlighting entrepreneurial lessons gleaned from political campaigns, parenthood, and even tee ball coaching.

We in the arts – and in all non-profit organizations really – draw on those skills every day. We manage volunteers with patience and excessively kind communication; we react nimbly to changing circumstances, both good and bad; and we persevere, fueled by the belief that we can improve the world, one tiny program at a time.

We’re pretty entrepreneurial, at least as long as we’re talking about entrepreneurial skills: patience, resolve, tenacity, determination, ingenuity, analytical thinking, and more.

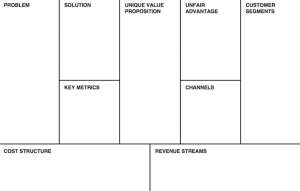

But it turns out we can make use of entrepreneurial tools as well, even if we don’t call ourselves Entrepreneurs. One tool in particular I’ve been using with arts organizations of late is the business model canvas (with some modifications).

The business model canvas is an approach to business planning that takes a typical business or strategic plan and maps it onto one page. (It does for a business plan what a dashboard does for a board meeting agenda.)

The concept was developed by the team at Strategyzer, particularly Alex Osterwalder, and the Business Model Generation website is full of useful blog updates, videos, and tools for download. There’s also a book and a host of additional resources if you’d like to learn more, not to mention related spinoffs, including Lean Canvas. The original business model canvas gave way to the Lean Canvas, created by Ash Maurya and captured on Lean Stack along with other tools and insights.

The entire canvas process boils down to a few key questions:

- What problem are you solving?

- Who has that problem (i.e., who are you serving)?

- How are you serving them?

- What do those services (service activities) cost?

- How are you monetizing those activities?

The answers – and a few more details – become the building blocks for a business model canvas: a one-page business plan snapshot of a company. (Plenty have argued that the snapshot is best suited for tech companies, but stick with me… A little creativity makes the concepts applicable to a host of other entities as well.)

But many leaders of organizations bristle at the thought of monetizing services, “customers” in general, and most of all, customer segments – key parts of the business model canvas. What’s more, many organizations don’t necessarily start by solving a problem. Instead, they start with the intention of delivering something amazing, without regard to competition (other organizations doing something similar) or market demand (are there enough supporters to justify the endeavor).

And frankly, that’s okay. But if the organization plans to subsist entirely on contributed income, its competitors will be applying for the same grants and approaching the same donors. And if it plans to have any stream of earned income, market demand becomes increasingly important.

After all, we can’t simply cut costs to survive – at least not if we plan on building something sustainable for the long-term. Cutting costs solves a short-term problem. Thinking through strategic implications of the organization reveals long-term solutions.

Our unique “value proposition” becomes a compelling story to share with funders, donors, and the public. In fact, it is community development, audience development, and even customer development in action.

I mentioned earlier that non-profit organizations don’t always start with a problem to solve; often they begin with passion. If that passion and determination can be a bit flexible – not too much, but a little – it can evolve into a really wonderful, creative solution to a problem. And with a few tweaks to the verbiage, and quite a bit of homage paid to the underlying ideas, the business model can help organizations think through their strategic plans and priorities.

And that solves all our problems.